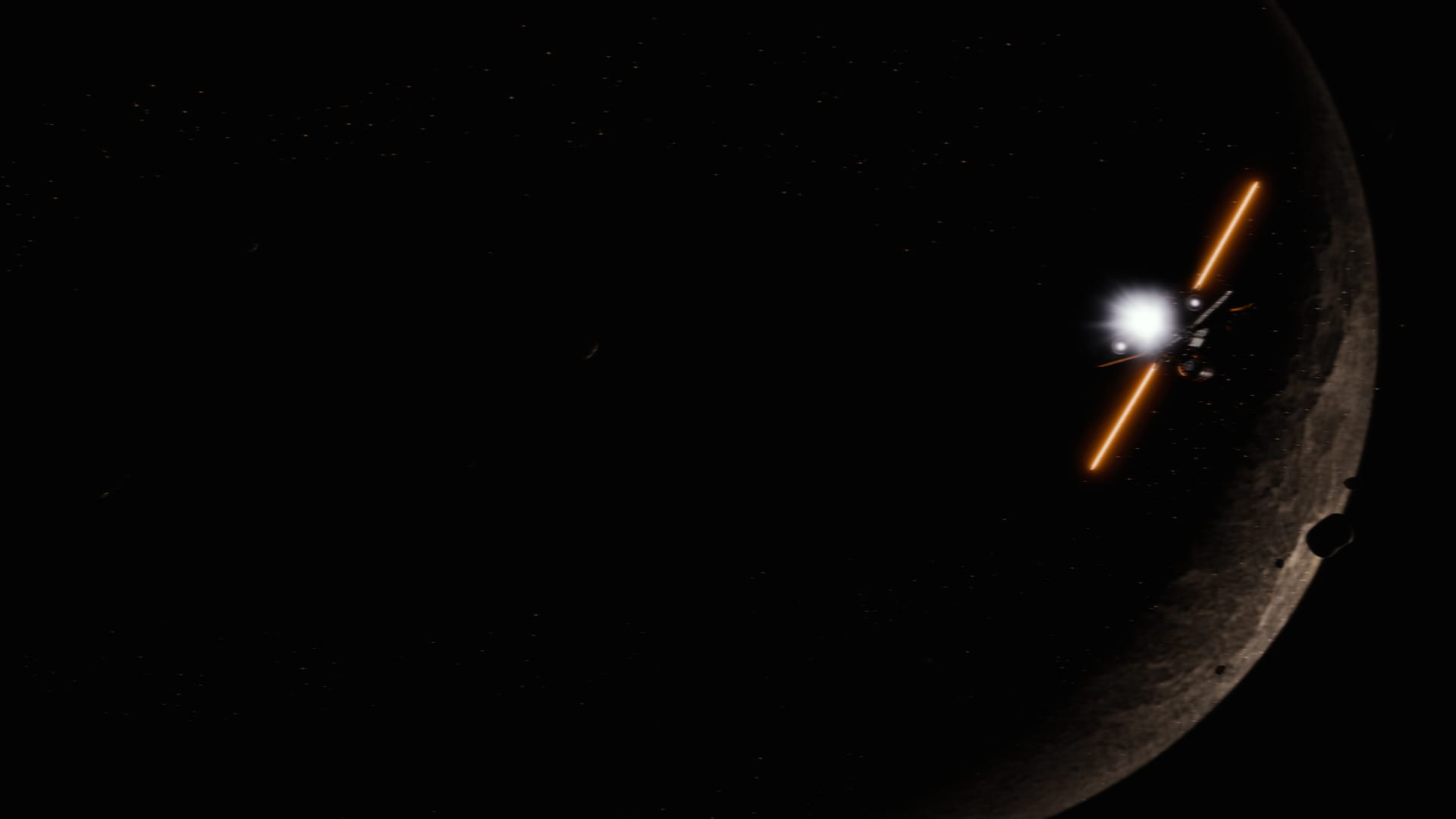

Even the most foundational astrography of the Astrild system is strategically unique. Dowager and its many orbiting planetoids present excellent opportunities for rapid response and fortification. The celestial ballet of moons that foreign astrographers have nicknamed the “Majestic Twelve'' make chained gravitational assist maneuvers possible in a way not seen in many other systems (and several racing circuits exist that satiate the Sibylean craving for gender neutral competition). The Royal Navy used all twelve hydrostatic satellites of Dowager to excellent effect during the Novani-Sibylean War. Hit-and-run tactics staged from the shadows kept the invading Republican Fleet on its toes, and the speed and ferocity of these strikes was amplified by the surprising maneuvers the Sibyleans could make given this home advantage. Royal Navy war doctrine has continued to emphasize the advantage of celestial clutter, and their already superbly built voidcraft have the edge necessary to occupy frequently superior numbers.

Because of the endless march of technological advance, the Royal Navy’s Admiralty saw fit to revamp their strike craft programs from the ground up sometime soon after The Detonation in 79 CY. It would be a decade until the superluminal implications of The Anomaly were fully understood, but the massive, strange voids snaking their way through The Bary also represented new opportunity and hazard in equal measure. It was quickly established that sensors could not penetrate these serpentine volumes of the abyss. Always mindful of their success defending against the Novani incursion not a century earlier, the RN desired a new fighter corps that was even more capable of using interstellar hedges to their advantage. That included extending the operational range of their strike and small craft beyond the immediate surrounds of Sibyl, something that had not been deemed a priority before.

The RN did have one unrated vessel capable of journeys beyond Sibylean high orbit. Their contemporary fleet of K-3E Lancer II combat cutters—voidcraft that were themselves a streamlined and perfected descendant of the legendary Lancer-class fast attack craft that had defended the homeworld—had the endurance the Admiralty desired. But of course, their K-4C Shortsword escort fighters did not, and confidence was low in the Lancer II’s ability to defend itself from harassment without escorts.

Rather than being practical and simply building a new and more synergistic escort fighter with added range on top of the old Shortsword platform, the RN Admiralty was as enticed as any foreign command by the fantasy of the “perfect combatant.” That is, they preferred to design a new fighter-interceptor to replace both at once. Sibyl’s explosive growth thanks to the increased pace of trade with other Barystates made this endeavor vaguely conceivable. Moreover, although they had their detractors in the Klatching and Regning, they had the interest of the reigning queen, whose was the only voice that mattered, and who had been troubled by early reports from The Anomaly.

In order to fulfill their new engineering objectives, the Sibylean Royal Defense Institute (SRDI) created the Advanced Endurance Interceptor (AEI) program in gyre 53 of 79 CY. In keeping with what they called ke vive, “alertness” or “readiness for anything,” the Admiralty laid out their requirements for a new generation of fighters capable of adapting to changing battlespace conditions. In keeping with a fiercely protective embrace of its homeworld, these voidcraft would also need to function perfectly well as aircraft. It would serve primarily as an endurance interceptor, but need to retain good dogfighting characteristics and serve in light strike roles if pressed.

A next generation fighter is only as effective as the sum quality of its parts, and the Admiralty had quite a few stringent asks for Her Majesty’s best engineers. Anxious to improve kill probability at medium to long range, the new platform’s laser weapons would need to be capable of engaging with combat-favorable irradiance and diffraction characteristics out to at least 40 kilometers. A voidborne delta-v of no less than 22,000 m/s was compulsory for the propulsion system, while it was also to carry a heavier Class 4 SRDI armor scheme. The package would not weigh more than 16,000 kg when fully loaded and should be able to stow its wings to a maximum storage width of 9 meters, such that it could be carried in sufficient numbers aboard House carrier vessels as well as aboard Royal Navy carrier fleets. Finally, the fighter would have a well-tested structural integrity sufficient for no less than fifty atmospheric re-entries between complete overhauls. In order to achieve this laundry list of lofty goals, the new strike craft would carry no consumables beyond its reaction mass, propellant, and life support supplies. Missiles, chaff, flares, and even ejectable heat sinks were eschewed in favor of making this work.

These characteristics would make the new voidcraft the lightest multi-role voidfighter built to date. No expense would be spared. But the Commonwealth was going through an unprecedented economic boom; there was no better time to begin.

As lavish in her spending on defense as on welfare and public works, Queen Avlynn the Third personally assured the necessary overheads for the project. The SRDI engineering team appointed to make the Admiralty’s fantasies a reality knew from the outset they would effectively have a blank check. But even with the welcome breathing room of capital costs secured well beyond initial projections, building a fighter like this was no small feat. No other known trans-atmospheric fighters in The Bary to this point could promise capabilities of this level simultaneously.

The project lead, one highly pragmatic and no-nonsense administrator by the name of Hanna Janis Malinsdottir, and her handpicked team of highly experienced aerospace engineers set to work, perhaps a bit nervous that the eyes of the Queen herself were upon them. By the middle of 82 CY, they had simulation-proved their blueprints of the XK-5, running all the calculations and scenario studies needed to ensure the production of a promising new entry into the Royal Navy’s legendary aerospace pantheon.

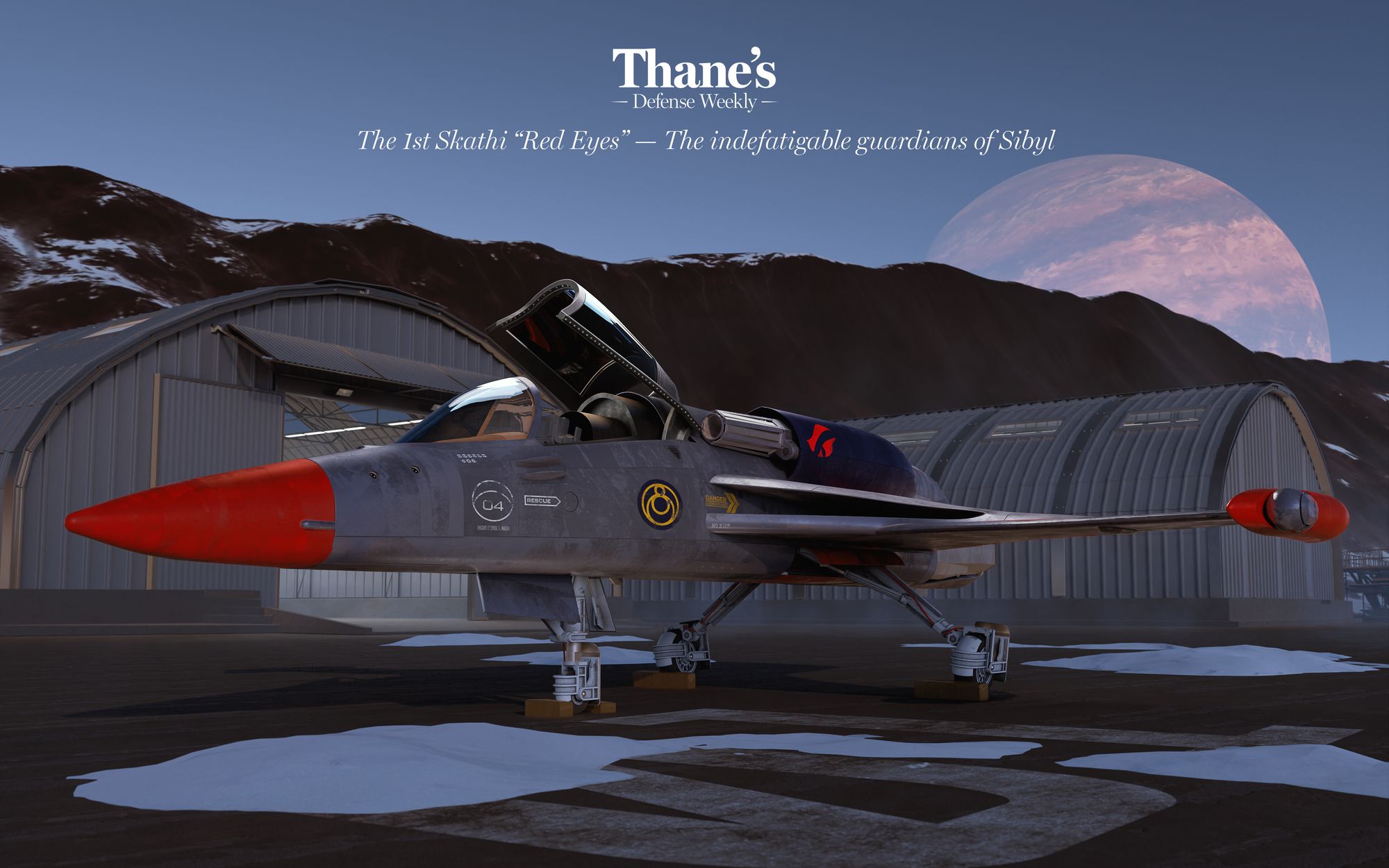

The XK-5 came with some very distinctive features, though the main body would resemble a conventional airframe for transonic and trans-atmospheric flight. Adding to the maneuverability of an already light airframe were a striking set of semi-balanced, forward-swept wings. More dramatic were the weapon systems stored at the end of its extent. A pair of bulbous wingtip pods each contained a compact (and hot, and expensive) KWF-3S pulsed point defense light laser turret. Another remarkable set of conformal weapon casings sit upon the upper fuselage, containing the fighter’s primary armament of two KWF-8M long-range sniper laser cannons.

Such peripheral features would of course require strengthened internal frameworks for the aerofoil in particular, and here the Sibyleans used their mastery of materials science and thermodynamics to great effect. A complex system of alloys, strategically placed about the craft, kept the aerofoils pliable under the added load of wingtip turrets. The mounts for these light off-bore Directed Energy Weapons are fascinating from a technical perspective in that they serve triple duty as an RCS blister and also as a vortex-reducing winglet. (Interestingly, the RCS plumbing is configured in such a way to allow for limited emergency cooling of these turrets.)

The flow-optimized structure of the air intakes curtailed much additional structural weakness in this aspect, and in any case the aerofoils were made a bit thicker to compensate, the additional parasitic drag presenting a minimal and acceptable downside for the vessel’s new engine cluster to power through. Delicate mass balancing helped to minimize the twisting motions undergone by the complex load on these wings.

Through some very careful consideration, Janis’ engineers had brewed a fighter that gained the benefit of added low-speed atmospheric maneuverability and increased voidborne roll response without sacrificing too much else. They were sure the Admiralty would be pleased, at least with their design documents. Now it was time to put theory into practice, a tense period of manufacturing, testing, and adjustment that daunts any aerospace team.

The first test flight was conducted by Dame Commander Felicia Herta Koresdottir on the Astrilish date 4th Rayspan, 42nd Gyre, 897 RE (84 CY). The design as manufactured showed great promise, but delays at newly-approved contractor Hex Machineworks forced the first test airframes to mount two SRDI Type-11M arcjet main thrusters borrowed from a K-4C Shortsword. These first airframes experience a more sluggish response in atmo and reduced delta-v performance in exoatmospheric conditions, and can be identified by their circular engine nacelles, compared to the rounded hexagonal nacelles of the final airframes’ dual Type-13M arcjets.

In the end, the otherwise conventional if somewhat overbuilt airframe of the XK-5 met instant success where it mattered most: flying. The engineering team at SRDI from the first flight on out could spend more time perfecting the actual combat capabilities of the aircraft than revisiting their old drawing boards. Much of this was due to Hanna Janis’ notoriety as a bureaucratic sorceress who gave her engineers all the resources they needed and ignored the sudden fanciful whims of the spectating Admiralty where appropriate.

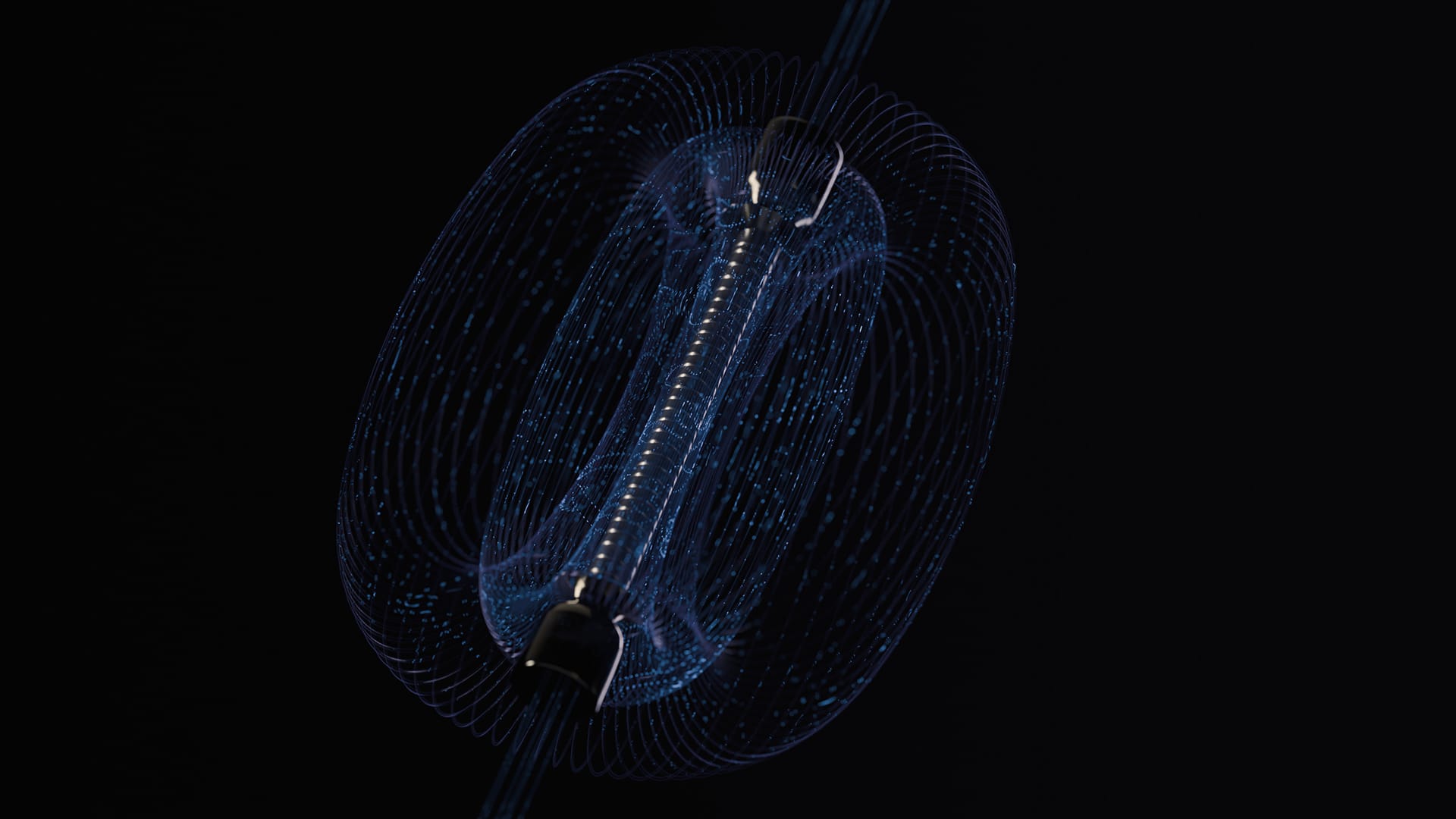

Developments later in the test program included sorting out bugs with navigation and tracking softwares, hardening the cockpit for Dowager’s radiation-rich environment, integrating the conformal weapon pods directly into the craft’s structure, shoring up teething issues with the magnetic thermal protection system, and finalizing the production design. After removing the ablative shielding on the test vehicles, the engineering team found they just barely met the Admiralty’s weight requirements, coming in under 16 tons ready for takeoff. This does leave the K-5 production model without a backup ablative aerobraking system for planetary re-entries. Some critics argue this is a dangerous safety rollback for a navy that regularly prides itself on the value of individual pilots.

The K-5 runs hot like all Sibylean designs, and even with its best-in-class PCM (Phase Change Material) heat sinks, brazen use of the weapons or engines can lock either up quickly. The Sibyleans design their strike craft to be used to their maximum potential by their best pilots; subsequently there’s little room for human error when flying them into engagements. Arguably more so than for any other atmospheric or voidfighter that has come before it, the K-5 requires the pilot to manage power and thermals when they could otherwise be focused on combat tactics. Sibylean dames and knights will all claim they can multitask while reciting lyrics from Thorra’s Saga backwards. Of course, occupational psychologists in the Royal Navy have their doubts, and have petitioned Admiralty to redress the issue and prepare contingencies to reduce task saturation for pilots.

One such improvement planned for the B model of the K-5 is a more robust computer system capable of managing the minutiae of these performance-critical tasks. A more complete software suite with modular master systems would also be responsible for automating the K-5s wingtip off-bore lasers. This would reduce task saturation to levels the RN Medical Corps are happier with, while also providing the craft with improved point defense against missiles or in dogfights. As of 100 CY, progress is once again being made in this area, having taken a backseat to refits for accompanying hyperspace modules.

As fitting for a marvel of Sibylean high technology and engineering prowess, the newly christened Crossbow—a name suggested by Felicia Herta herself—is an expensive beast to produce and maintain. It rounded out to 18,000,000 Sibylean crowns mean cost per unit, a 38% cost increase per unit over the K-4C Shortsword it is meant to replace. Now in production, the K-5A is also, by all means, that much more capable in the right hands. The K-4C had 70% the delta-v, weaker armor, 16% less atmospheric thrust, a missile-dependent outfitting, and an airframe rated for far fewer re-entries and supersonic flights before regular hull maintenance.

DACT engagements late into testing showed that the K-4 could still hold its own in a close-in dogfight, but it was hopelessly matched against the K-5’s superior laser systems at range—particularly in vacuum—and the K-5 had the thrust advantage in both the airborne and voidborne regimes to maintain that distance indefinitely. Put another way, though the K-5 was still just as capable of winning a simulated dogfight with a talented dame or knight on the stick and throttle, it established dominance in a BVR fight. The Admiralty and the Queen herself were of course very pleased.

Since the beginning of interplanetary warfare and certainly since the Novani-Sibylean conflict, the Sibylean Royal Navy has put the strongest weapons possible in the hands of their esteemed but small population of pilot knights. Only in the past couple of decades, with its bustling economy, has Sibyl been able to afford such extravagant new designs that will allow them to traverse up and down their many gravity wells with ease, fighting and in many cases outmaneuvering any intruders along the way.